"Put Me In The Picture" by Valerie Grove. Originally published in The Sunday Times Magazine, May 1 2011

It wasn't my idea. Like many people, I regarded having ones portrait painted as an act of vanity, extravagance and tedium. It is only thanks to June Mendoza's persistence that one of her three portraits in this years Royal Society of Portrait Painters exhibition is of me. She'd been asking me to sit for at least 20 years. Every year Id go to the exhibition, admire her latest work Judi Dench, Tom Stoppard, Victoria Glendinning then fob her off with too busy, no time. And then, last August, I said okay.

It couldn't be vanity, or I wouldn't have left it this late; its more a matter of curiosity. People react so interestingly to their portraits. Germaine Greer admires Paula Regos intelligent version of her in the National Portrait Gallery listening intently, knees splayed, soles of shoes locked together while David Hare found Regos portrait of him sprawled in an armchair, eyes downcast, hand on heart distressing. I have heard AS Byatt talk about why she loves Patrick Herons childlike abstract of her because it gives the presence of the idea of me, which is true. That's what portrait painting is really about. So without trepidation I offered myself into the hands of Mendoza.

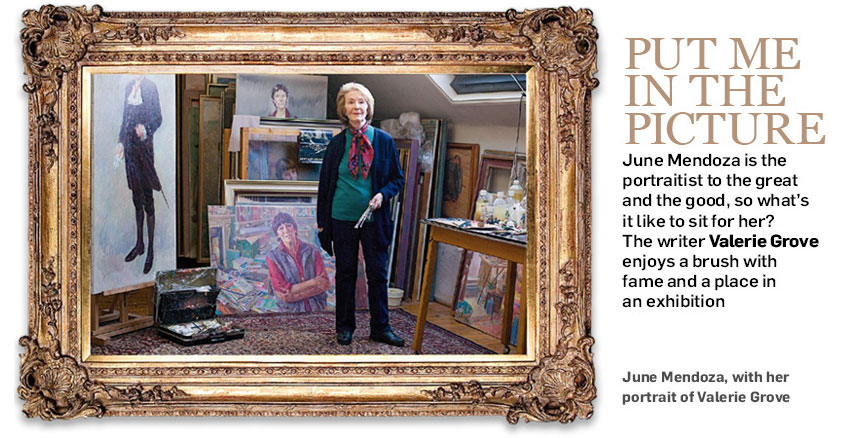

She's quick, neat and bird-like, with beautiful diction and clear hazel eyes. The doyenne of portraitists, she has painted a packed House of Commons (440 likenesses) and most royals, archbishops, prime ministers and judges, as well as grandees of the stage, opera house and concert hall. She must be of a certain age, but says firmly: No birth dates, dear.

First she had to check out my wardrobe. I presented a rack of jackets you could call vintage, and my favourite scarlet Chinese embroidered silk, with its grim association: it caught my eye in a Fulham shop window in 1999 while I was reporting on the murder of Jill Dando. Im not painting that, said Mendoza, in her forthright Australian way. I shall do you as you are. Woe! I was in workaday dog-walking clothes: jeans, red shirt, grey padded waistcoat all bought by mail order. Im doing a portrait of you, she said, not a picture of you dressed up as something else. Otherwise why bother just making a pretty painting?

Where would I sit? My parlour has the kind of grown-up sofas seen in portraits, but it was full of bikes and prams, as usual, plus unwelcome sunlight. It had to be my sunless study. Mendoza brushed aside the chaos, stepping over piles of magazines and books and baskets: You are not a boardroom portrait, dear. Refusing help, she set up her unwieldy old easel, shooed the dog away and decided I was to stand, one buttock resting against a bookshelf, arms folded. Just keep talking, she said.

Martin Gayford, who has written a riveting book Man with a Blue Scarf on sitting for Lucian Freud, likens the experience to somewhere between transcendental meditation and a visit to the barbers. I found it more like one of those talking cures the NHS commends to the depressed: both confessional and therapeutic.

On day one we talked of death. Mendoza's friend Dame Joan Sutherland, whose famous portrait in the title role of Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizettis tragic opera) she'd painted, was fading. I had just heard that someone I care terribly about was not, after all, at deaths door. In the previous days, misery had etched itself into my face: I did not want this melancholy visage to be immortalised in oil; but just before the appointed hour I had a good-news email there had been a reprieve, and a homecoming, and my friend and I would meet again after all. So my mood lifted, the talking could begin.

There was no shortage of subjects. We had many people in common, some Id interviewed and she'd painted Zoe Wanamaker, Jeffrey Archer and David Mellor (whose amazing riverside house is the real focus of her portrait). Mendoza's Barry Humphries portrait had remained unfinished, but her mother had played his sidekick Madge Allsopp in an early tour of Dame Edna; and she'd once seen Sir Les Patterson's appendage swinging in his dressing room. When my fax machine spewed out a note from the cartoonist Ronald Searle, she said she'd love to do him. (Searle, who at 91 cherishes his seclusion in the south of France, told me to tell her she can come in 2020.) Our sittings stretched over six months. I started with a tan and finished with a wintry pallor. Her stamina was amazing. One day I noted in my diary: She arrived at 11am, having driven all the way from Wimbledon in her little Suzuki wagon, and left at 3.30 In all that time she had one cup of tea and one pee.

I asked whether she'd enjoyed chatting with the Queen, whom she's painted twice. She was sure she had, but couldn't recall. Im concentrating on the painting, she said. I don't remember any of the conversation afterwards. In 2004 she went to the palace to get her OBE. She never wears skirts or hats, but she had found a wonderful trilby in a charity shop in Castle Douglas for 20p. A palace flunky told her she was the smartest person there.

Mendoza was born in Melbourne, with a natural talent for drawing people, or animals, anything with life in them. At 14 she joined a life class, in her school uniform and plaits. I was bovine, dear a very obedient child. My mother was a bit concerned about me seeing a nude male, but apparently I didn't bat an eyelid.

Her parents, the Mortons, were theatre musicians who separated when she was six. Dot, a pianist, reverted to her maiden name, Mendoza, a good stage name. June became a backstage kid, brazen enough to persuade Sir Malcolm Sargent to sit for her. When Dot took her daughter on tour with the De Basil Russian Ballet, June learnt choreography and had a small part in Petrushka. I lived and breathed ballet. It was design, colour, movement and an introduction to Brahms, Prokofiev, Schumann. I still see certain steps when I hear the music.

I have known Mendoza's work since the 1950s, because her first job, after coming to London to study at St Martins, was drawing Belle of the Ballet in the comic Girl, which was read by every little girl in the land. The strips previous artist told her she'd go round the bend within two years. And I did five years. But it was a fantastic job because at this point I didn't have a bus fare. Id arrived with 30 quid. She lived in Kangaroo Valley, of course, with a gas ring and four budgies. Once, in her Earls Court days, she needed to pay a doctor and did drawings of his children instead. I love the barter system: you both get what you want out of it. She also appeared in the West End (she had acted in Sydney) in Me and My Girl, with Lupino Lane, but she never stopped drawing. She also got married, thrice: first to a fellow actor, then to a man who died of a brain tumour three years later, And then Keith came into my life. Keith Mackrell is now a governor of the LSE, where he had been a Harold Laski scholar and got a first. He is now retired from Shell International.

After their honeymoon in 1960 they were posted to the Philippines, to an expat life. Beautiful house, hot-and-cold running servants it wasn't me at all. I never learnt how to be a memsahib. But I could get out of those dreaded coffee parties because I was a mad artist. Painting portraits, I had the whole country to myself, and it allowed me to cross every social barrier. They left just in time, as their four children (daughters Elliet and Kim, son, Ashley, and a daughter, Lee, adopted at 13 days old) were beginning to see other children ordering servants about. It was good to get them back to reality.

By the 1970s, Mendoza was painting plenty of actors and musicians. For a while she was the only woman in the Royal Society of Portrait Painters (RSPP): now there are eight, out of 51 members. Once, with four young children at home, she did three solid years of bread-and-butter boardroom commissions. I wouldn't go through that pressure again for anything. I started to get stale. She now ensures that one-third of her work is self-generated, painting anyone who catches her eye. She calls these her pick-ups, and I was one of them. She's forgotten how we met (I went to see her in Wimbledon in 1984, when researching a book about career women with families). And Id never, until now, enquired why she'd wanted to paint me. She replied, rather embarrassingly: Some artists choose St Paul's at Sunset. I choose people. I like people. I liked you; your personality/character was individual, as was your appearance, and I admired you. So I asked. And Im absolutely delighted I did.

Even if she had no commissions, she would carry on picking people up. I am not a lady who lunches I haven't got time but once, at a lunch, I stopped an elegant black lady and said, God, you're so elegant, would you sit for me? and she turned out to be Madeline Bell, the jazz singer, so of course I had a ball with her.

According to Sandy Nairne, director of the National Portrait Gallery, commissioning portraits is increasingly popular, partly as a reaction to digital photography. Annabel Elton, who deals with commissions for members of the RSPP, says enquiries from sitters increase every year (apart from a blip in 2010 during the banking crisis). People expect to pay around 7,000; a few artists can charge 50,000 or more. Mendoza charges 3,000-18,000 for an oil painting, depending on size and complexity. Elton has had her own portrait painted six times, and likens the process to being pregnant: Youre being incredibly creative while doing nothing at all.

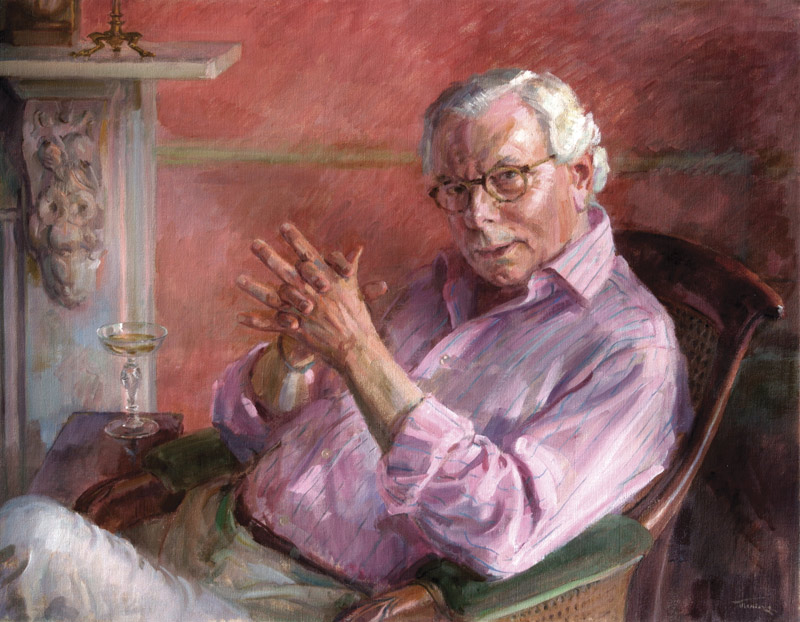

In this years RSPP exhibition in the Mall Galleries (three oil paintings per artist), Mendoza is also exhibiting the mezzo-soprano Dame Felicity Palmer I've painted about 50 musicians, music being my thing and Dr David Starkey. Since Starkey was about to make a Channel 4 programme about royal portraiture for the series The Genius of British Art, he suggested she should be filmed painting him. This took place by his fireplace in north London with a Venetian champagne glass to hand. Alas, most of the Mendoza sequence ended on the cutting-room floor. But Starkey did say, apropos of Holbein painting Erasmus, that a portrait painter must capture not just the appearance and character of the sitter, but the very soul.

Mendoza pondered this. Well, she said, I've got a blank canvas, a palette of colours and different brushes. You need to get some communication, and its up to me to observe their body language, the way they move and place themselves. Then there's the design, the background, the aspect, and your decision on colour. We may go for character, and were certainly going for a painting. Im not sure we have time to consider their soul.

I ask Mendoza her view of artists who paint from photographs. A lot of people turn out competent, wonderful stuff that way, but I can't work like that. I want nothing in between me and the person. When I see a beautiful portrait done from blown-up photographs, I think, That must have been a splendid photograph. Why don't they use the photograph?

If sitting for a portrait is like pregnancy, the end is like birth wondering what's going to come out. Do people always like their portraits? Oh, God, I shouldn't think so, Mendoza said. But I know whether Im satisfied, and that's the way its got to be.

By last December, I thought Mendoza already had me bang to rights, but she said, Oh, it will get worse before it gets better, and proceeded to add some dismaying sags and lines. She also needed a session without me, to fill in the background mess. Then, one day in January, she finally said: That's it. Got it. Really? Yes, indeed. And everyone agreed it was absolutely me, including me.

June Mendoza's portraits of Valerie Grove, Dr David Starkey and Dame Felicity Palmer feature in the Royal Society of Portrait Painters annual exhibition at the Mall Galleries, London SW1, May 5-2o